The subtitle of the English translation of Julius Evola’s Ride the Tiger (Cavalcare la Tigre) promises that it offers “A Survival Manual for the Aristocrats of the Soul.”[1] [2] As a result, one comes to the work with the expectation that it will constitute a kind of “self-help book” for Traditionalists, for “men against time.” One expects that Evola will offer moral support and perhaps even specific instructions for revolting against the modern world. Unfortunately, the subtitle proves misleading. Ride the Tiger is primarily devoted to an analysis of aspects of the present age of decline (the Kali Yuga): critiques of relativism, scientism, modern art, modern music, and of figures like Heidegger and Sartre; discussions of the decline of marriage, the relation between the sexes, drug use, and so forth. Many of the points Evola makes in this volume are made in his other works, sometimes at greater length and more lucidly.

For those seeking something like a “how to” guide for living as a Traditionalist, it is mainly the second division of the book (“In the World Where God is Dead”) that offers something, and chiefly it is to be found in Chapter Eight: “The Transcendent Dimension – ‘Life’ and ‘More than Life.’” My purpose in this essay is to piece together the miniature “survival manual” provided by Chapter Eight – some of which consists of little more than hints, conveyed in Evola’s often frustratingly opaque style. It is my view that what we find in these pages is of profound importance for anyone struggling to hold on to his sanity in the face of the decadence and dishonesty of today’s world. It is also essential reading for anyone seeking to achieve the ideal of “self-overcoming” taught by Evola – seeking, in other words, to “ride the tiger.”

For those seeking something like a “how to” guide for living as a Traditionalist, it is mainly the second division of the book (“In the World Where God is Dead”) that offers something, and chiefly it is to be found in Chapter Eight: “The Transcendent Dimension – ‘Life’ and ‘More than Life.’” My purpose in this essay is to piece together the miniature “survival manual” provided by Chapter Eight – some of which consists of little more than hints, conveyed in Evola’s often frustratingly opaque style. It is my view that what we find in these pages is of profound importance for anyone struggling to hold on to his sanity in the face of the decadence and dishonesty of today’s world. It is also essential reading for anyone seeking to achieve the ideal of “self-overcoming” taught by Evola – seeking, in other words, to “ride the tiger.”

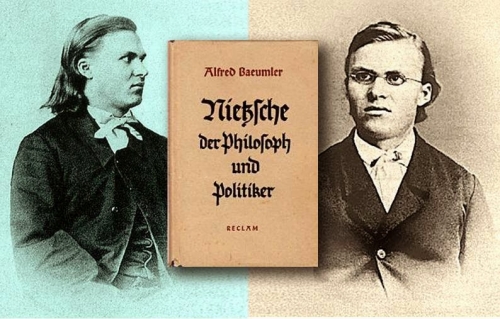

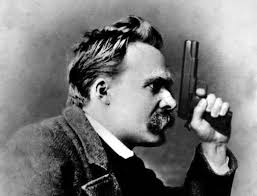

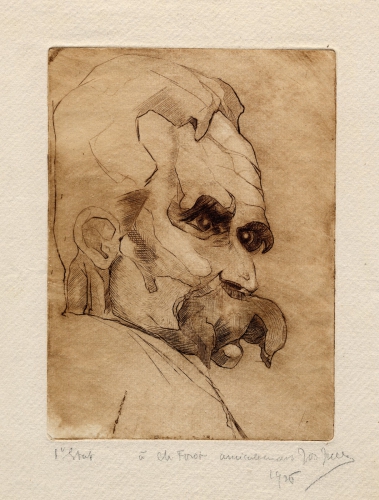

The central figure of the book’s second part is unquestionably Friedrich Nietzsche, to whom Evola repeatedly refers. Evola’s attitude toward Nietzsche is critical. However, it is obvious that Nietzsche exercised a profound and positive influence on him. Indeed, virtually every recommendation Evola makes for living as a Traditionalist – in this section of the work, at least – is somehow derived from Nietzsche. This despite the fact that Nietzsche was not a Traditionalist – a fact of which Evola was well aware, and to which I shall turn later.

In the last paragraph of Chapter Seven, Evola announces that in the next chapter he will consider “a line of conduct during the reign of dissolution that is not suitable for everyone, but for a differentiated type, and especially for the heir to the man of the traditional world, who retains his roots in that world even though he finds himself devoid of any support for it in his outer existence.”[2] [3] This “line of conduct” turns out, in Chapter Eight, to be based entirely on statements made by Nietzsche. That chapter opens with a continuation of the discussion of the man who would be “heir to the man of the traditional world.” Evola writes, “What is more, the essential thing is that such a man is characterized by an existential dimension not present in the predominant human type of recent times – that is, the dimension of transcendence.”[3] [4]

Evola clearly regarded this claim as of supreme importance, since he places the entire sentence just quoted in italics. The sentence is important for two reasons. First, as it plainly asserts, it provides the key characteristic of the “differentiated type” for whom Evola writes, or for whom he prepares the ground. Second, the sentence actually provides the key point on which Evola parts company with Nietzsche: for all the profundity and inspiration Nietzsche can provide us, he does not recognize a “dimension of transcendence.” Indeed, he denigrates the very idea as a projection of “slave morality.” Our first step, therefore, must be to understand exactly what Evola means by “the dimension of transcendence.” Unfortunately, in Ride the Tiger Evola does not make this very easy. To anyone familiar with Evola’s other works, however, his meaning is clear.

“Dimension of transcendence” can be understood as having several distinct, but intimately-related meanings in Evola’s philosophy. First, the term “transcendence” simply refers to something existing apart from, or beyond the world around us. The “aristocrats of the soul” living in the Kali Yuga must live their lives in such a way that they “stand apart from” or transcend the world in which they find themselves. This is the meaning of the phrase “men against time,” which I have already used (and which derives from Savitri Devi). The “differentiated type” of which Evola writes is one who has differentiated himself from the times, and from the men who are like “sleepers” or pashu (beasts). Existing in the world in a physical sense, even playing some role (or roles) in that world, one nevertheless lives wholly apart from it at the same time, in a spiritual sense. This is the path of those who aim to “ride the tiger”: they do not separate themselves from the decay, like monks or hermits; instead they live in the midst of it, but remain uncorrupted. (This is also little different from what the Gurdjieffian tradition calls “the fourth way,” and it is the essence of the “Left-Hand Path” as described by Evola and others.)

However, there is another, deeper sense of the “dimension of transcendence.” The type of man of which Evola speaks is not simply reacting to the world in which he finds himself. This is not what his “apartness” consists in – not fundamentally. Nor does it consist in some kind of intellectual commitment to a “philosophy of Traditionalism,” as found in books by Evola and others. Rather, “transcendence” in the deepest sense refers to the Magnum Opus that is the aim of the “magic” or spiritual alchemy discussed by Evola in his most important works (chiefly Introduction to Magic and The Hermetic Tradition). “Transcendence” means the overcoming of the world and of the ego – really, of all manifestation, whether it is objective (“out there”) or subjective (“in here”). Such overcoming is the work of what is called in Vedanta the “witnessing consciousness.” Evola frequently calls this “the Self.” (For more on this teaching, see my essays “What is Odinism? [5]” in TYR, Vol. 4 [6], and “On Being and Waking” in TYR, Vol. 5, forthcoming [7].)

These different senses of “transcendence” are intertwined. It is only through the second sense of “transcendence,” of the overcoming of all manifestation, that the first sense, standing apart from the modern world, can truly be achieved. The man who is “heir to the man of the traditional world” can retain “his roots in that world” only by the achievement of a state of being that is identical to that of the “highest type” of the traditional world. That type was also “differentiated”: set apart from other men. Fundamentally, however, to be a “differentiated type” does not mean to be differentiated from others. It refers to the state of one who has actively differentiated “himself” from all else, including “the ego.” This active differentiation is the same thing as “identification” with the Self – which, for Evola, is not the dissolution of oneself in an Absolute Other, but the transmutation of “oneself” into “the Self.” Further, the metaphysical differentiation just described is the only sure and true path to the “differentiation” exhibited by the man who lives in the Kali Yuga, but stands apart from it at the same time.

Much later I will discuss how and why Nietzsche fails to understand “the dimension of transcendence,” and how it constitutes the fatal flaw in his philosophy. Recognizing this, Evola nonetheless proceeds to draw from Nietzsche a number of principles which constitute the spirit of “the overman.”[4] [8] Evola offers these as characterizing his own ideal type – with the crucial caveat that, contra Nietzsche, these principles are only truly realizable in a man who has realized in himself the “dimension of transcendence.” Basically, there are ten such principles cited by Evola, each of which he derives from statements made by Nietzsche. The passage in which these occur is highly unusual, since it consists in one long sentence (lasting more than a page), with each principle set off by semi-colons. I will now consider each of these points in turn.

1. “The power to make a law for oneself, the ‘power to refuse and not to act when one is pressed to affirmation by a prodigious force and an enormous tension.’”[5] [9] This first principle is crucial, and must be discussed at length. Earlier, in Chapter Seven (“Being Oneself”), Evola quotes Nietzsche saying, “We must liberate ourselves from morality so that we can live morally.”[6] [10] Evola correctly notes that in such statements, and in the idea of “making a law for oneself,” Nietzsche is following in the footsteps of Kant, who insisted that genuine morality is based upon autonomy – which literally means “a law to oneself.” This is contrasted by Kant to heteronomy (a term Evola also uses in this same context): morality based upon external pressures, or upon fealty to laws established independent of the subject (e.g., following the Ten Commandments, conforming to public opinion, acting so as to win the approval of others, etc.). This is the meaning of saying, “we must liberate ourselves from morality [i.e., from externally imposed moral commandments] so that we can live morally [i.e., autonomously].” In order for the subject’s standpoint to be genuinely moral, he must in a sense “legislate” the moral law for himself, and affirm it as reasonable. Indeed, for Kant, ultimately the authority of the moral law consists in our “willing” it as rational.

Of course, Nietzsche’s position is not Kant’s, though Evola is not very helpful in explaining to us what the difference consists in. He writes that Nietzsche’s notion of autonomy is “on the same lines” as Kant’s “but with the difference that the command is absolutely internal, separate from any external mover, and is not based on a hypothetical law extracted from practical reason that is valid for all and revealed to man’s conscience as such, but rather on one’s own specific being.”[7] [11] There are a good deal of confusions here – so much so that one wonders if Evola has even read Kant. For instance, Kant specifically rejects the idea of an “external mover” for morality (which is the same thing as heteronomy). Further, there is nothing “hypothetical” about Kant’s moral law, the “categorical imperative,” which he specifically defines in contrast to “hypothetical imperatives.” We may also note the vagueness of saying that “the command” must be based “on one’s specific being.”

Still, through this gloom one may detect exactly the position that Evola correctly attributes to Nietzsche. Like Kant, Nietzsche demands that the overman practice autonomy, that he give a law to himself. However, Kant held that our self-legislation simultaneously legislates for others: the law I give to myself is the law I would give to any other rational being. The overman, by contrast, legislates for himself only – or possibly for himself and the tiny number of men like him. If we recognize fundamental qualitative differences between human types, then we must consider the possibility that different rules apply to them. Fundamental to Kant’s position is the egalitarian assertion that people do not get to “play by their own rules” (indeed, for Kant the claim to be an exception to general rules, or to make an exception for oneself, is the marker of immorality). If we reject this egalitarianism, then it does indeed follow that certain special individuals get to play by their own rules.

Still, through this gloom one may detect exactly the position that Evola correctly attributes to Nietzsche. Like Kant, Nietzsche demands that the overman practice autonomy, that he give a law to himself. However, Kant held that our self-legislation simultaneously legislates for others: the law I give to myself is the law I would give to any other rational being. The overman, by contrast, legislates for himself only – or possibly for himself and the tiny number of men like him. If we recognize fundamental qualitative differences between human types, then we must consider the possibility that different rules apply to them. Fundamental to Kant’s position is the egalitarian assertion that people do not get to “play by their own rules” (indeed, for Kant the claim to be an exception to general rules, or to make an exception for oneself, is the marker of immorality). If we reject this egalitarianism, then it does indeed follow that certain special individuals get to play by their own rules.

This does not mean that for the self-proclaimed overman “anything goes.” Indeed, any individual who would interpret the foregoing as licensing arbitrary self-indulgence of whims or passions would be immediately disqualified as a potential overman. This will become crystal clear as we proceed with the rest of Evola’s “ten principles” in Chapter Eight. For the moment, simply look once more at the wording Evola borrows from Nietzsche in our first “principle”: the “power to refuse and not to act when one is pressed to affirmation by a prodigious force and an enormous tension.” To refuse what? What sort of force? What sort of tension? The claim seems vague, yet it is actually quite clear: autonomy means, fundamentally, the power to say no to whatever forces or tensions press us to affirm them or give way to them.

The “forces” in question could be internal or external: they could be the force of social and environmental circumstances; they could be the force of my own passions, habits, and inclinations. It is a great folly to think that my passions and such are “mine,” and that in following them I am “free.” Whatever creates an “enormous tension” in me and demands I give way, whether it comes from “in me” or “outside me” is precisely not mine. Only the autonomous “I” that can see this is “mine,” and only it can say no to these forces. It has “the power to refuse and not to act.” Essentially, Nietzsche and Evola are talking about self-mastery. This is the “law” that the overman – and the “differentiated type” – gives to himself. And clearly it is not “universalizable”; the overman does not and cannot expect others to follow him in this.[8] [12]

In short, this first principle asks of us that we cultivate in ourselves the power to refuse or to negate – in one fashion or other – all that which would command us. Again, this applies also to forces within me, such as passions and desires. Such refusal may not always amount to literally thwarting or annihilating forces that influence us. In some cases, this is impossible. Our “refusal” may sometimes consist only in seeing the force in question, as when I see that I am acting out of ingrained habit, even when, at that moment, I am powerless to resist. Such “seeing” already places distance between us and the force that would move us: it says, in effect, “I am not that.” As we move through Evola’s other principles, we will learn more about the exercise of this very special kind of autonomy.

2. “The natural and free asceticism moved to test its own strength by gauging ‘the power of a will according to the degree of resistance, pain, and torment that it can bear in order to turn them to its own advantage.’”[9] [13] Here we have another expression of the “autonomy” of the differentiated type. Such a man tests his own strength and will, by deliberately choosing that which is difficult. Unlike the Last Man, who has left “the regions where it is hard to live,”[10] [14] the overman/differentiated man seeks them out.

Evola writes that “from this point of view everything that existence offers in the way of evil, pain, and obstacles . . . is accepted, even desired.”[11] [15] This may be the most important of all the points that Evola makes in this chapter – and it is a principle that can serve as a lifeline for all men living in the Kali Yuga, or in any time. If we can live up to this principle, then we have made ourselves truly worthy of the mantle of “overman.” The idea is this: can I say “yes” to whatever hardship life offers me? Can I use all of life’s suffering and evils as a way to test and to transform myself? Can I forge myself in the fire of suffering? And, going a step further, can I desire hardship and suffering? It is one thing, of course, to accept some obstacle or calamity as a means to test myself. It is quite another to actively desire such things.

Here we must consider our feelings very carefully. Personally, I do not fear my own death nearly as much as the death of those close to me. And I fear my own physical incapacitation and decline more than death. Is it psychologically realistic for me to desire the death of my loved ones, or desire a crippling disease, as a way to test myself? No, it is not – and this is not what Evola and Nietzsche mean. Rather, the mental attitude in question is one where we say a great, general “yes” to all that life can bring in the way of hardship. Further, we welcome such challenges, for without them we would not grow. It is not that we desire this specific calamity or that, but we do desire, in general, to be tested. And, finally, we welcome such testing with supreme confidence: whatever life flings at me, I will overcome. In a sense, I will absorb all negativity and only grow stronger by means of it.

3. Evola next speaks of the “principle of not obeying the passions, but of holding them on a leash.” Then he quotes Nietzsche: “greatness of character does not consist in not having such passions: one must have them to the greatest degree, but held in check, and moreover doing this with simplicity, not feeling any particular satisfaction thereby.”[12] [16] This follows from the very first principle, discussed earlier. To repeat, giving free rein to our passions has nothing to do with autonomy, freedom, or mastery. Indeed, it is the primary way in which the common man finds himself controlled.

To see this, one must be able to recognize “one’s own” passions as, in reality, other. I do not choose these things, or the power they exert. What follows from this, however, is not necessarily thwarting those passions or “denying oneself.” As Evola explains in several of his works, the Left-Hand Path consists precisely in making use of that which would enslave or destroy a lesser man. We hold the passions “on a leash,” Evola says. The metaphor is appropriate. Our passions must be like well-trained dogs. Such animals are filled with passionate intensity for the chase – but their master controls them completely: at a command, they run after their prey, but only when commanded. As Nietzsche’s words suggest, the greatest man is not the man whose passions are weak. A man with weak passions finds them fairly easy to control! The superior man is one whose passions are incredibly strong – one in whom the “life force” is strong – but who holds those passions in check.

4. Nietzsche writes, “the superior man is distinguished from the inferior by his intrepidity, by his defiance of unhappiness.”[13] [17] Here too we have invaluable advice for living. The intrepid man is fearless and unwavering; he endures. But why does Nietzsche connect this with “defiance of unhappiness”? The answer is that just as the average man is a slave to the passions that sweep him away at any given time, so he is also a prisoner of his “moods.” Most men rise in the morning and find themselves in one mood or another: “today I am happy,” “today I am sad.” They accept that, in effect, some determination has been made for them, and that they are powerless in the matter. If the unhappiness endures, they have a “disease” which they look to drugs or alcohol to cure.

As with the passions, the average man “owns” his moods: “this unhappiness is mine, it is me,” he says, in effect. The superior man learns to see his moods as if they were the weather – or, better yet, as if they were minor demons besetting him: external mischief makers, to whom he has the power to say “yes” or “no.” The superior man, upon finding that he feels unhappiness, says “ah yes, there it is again.” Immediately, seeing “his” unhappiness as other – as a habit, a pattern, a kind of passing mental cloud – he refuses identification with it. And he sets about intrepidly conquering unhappiness. He will not acquiesce to it.

As with the passions, the average man “owns” his moods: “this unhappiness is mine, it is me,” he says, in effect. The superior man learns to see his moods as if they were the weather – or, better yet, as if they were minor demons besetting him: external mischief makers, to whom he has the power to say “yes” or “no.” The superior man, upon finding that he feels unhappiness, says “ah yes, there it is again.” Immediately, seeing “his” unhappiness as other – as a habit, a pattern, a kind of passing mental cloud – he refuses identification with it. And he sets about intrepidly conquering unhappiness. He will not acquiesce to it.

5. The above does not mean, however, that the superior man intrepidly sets about trying to make himself “happy.” Evola quotes Nietzsche as saying “it is a sign of regression when pleasure begins to be considered as the highest principle.”[14] [18] The superior man responds with incredulity to those who “point the way to happiness,” and respond, “But what does happiness mean to us?”[15] [19] The preoccupation with “happiness” is characteristic of the inferior modern type Nietzsche refers to as “the Last Man” (“‘We have invented happiness,’ say the last men, and they blink. They have left the regions where it was hard to live, for one needs warmth.”[16] [20]

But if we do not seek happiness, in the name of what do we “defy unhappiness”? Answer: in the name of greatness, self-mastery, self-overcoming. Kant can be of some limited help to us here as well, for he said that the aim of life should not be happiness, but making oneself worthy of happiness. Many individuals may achieve happiness (actually, the dumber one is, the greater one’s chances). But only some are worthy of happiness. The superior man is worthy of happiness, whether he has it or not. And he does not care either way. He does not even aim, really, to be worthy of happiness, but to be worthy of greatness, like Aristotle’s “great-souled man” (megalopsuchos).[17] [21]

6. According to Evola, the superior man claims the right (quoting Nietzsche) “to exceptional acts as attempts at victory over oneself and as acts of freedom . . . to assure oneself, with a sort of asceticism, a preponderance and a certitude of one’s own strength of will.”[18] [22] This point is related to the second principle, discussed earlier. The superior man is master, first and foremost, of himself. He therefore seeks opportunities to test himself in exceptional ways. Evola provides an extended discussion of one form of such self-testing in his Meditations on the Peaks: Mountain Climbing as Metaphor for the Spiritual Quest (and, of course, for Evola mountain climbing was not entirely metaphorical!). Through such opportunities, one “assures oneself” of the strength of one’s will. But there is more: through such tests, one’s will becomes even stronger.

“Asceticism” suggests self-denial. But how does such testing of the will constitute “denying oneself”? The key, of course, lies in asking “what is my self?” The self that is denied in such acts of “self-mastery” is precisely the self that seeks to hold on to life, to safety, to security, and to its ephemeral preoccupations and possessions. We “deny” this self precisely by threatening what it values most. To master it is to progressively still its voice and loosen its hold on us. It is in this fashion that a higher self – what Evola, again, calls the Self – grows in us.

7. The superior man affirms the freedom which includes “keeping the distance which separates us, being indifferent to difficulties, hardships, privations, even to life itself.”[19] [23] This mostly reaffirms points made earlier. But what is “the distance that separates us”? Here Nietzsche could be referring to hierarchy, or what he often calls “the order of rank.” He could also be referring to the well-known desire of the superior man for apartness, verging sometimes on a desire for isolation. The superior man takes himself away from others; he has little need for the company of human beings, unless they are like himself. And even then, he desires the company of such men only in small and infrequent doses. He is repulsed by crowds, and by situations that force him to feel the heat and breath and press of others. Such feelings are an infallible marker of the superior soul – but they are not a “virtue” to be cultivated. One either has such feelings, or one does not. One is either the superior type, or a “people person.”

If we consult the context in which the quote appears – an important section of Twilight of the Idols – Nietzsche offers us little help in understanding specifically what he means by “the distance that separates us.” But the surrounding context is a goldmine of reflections on the superior type, and it is surprising that Evola does not quote it more fully. Nietzsche remarks that “war educates for freedom” (a point on which Evola reflects at length in his Metaphysics of War), then writes:

If we consult the context in which the quote appears – an important section of Twilight of the Idols – Nietzsche offers us little help in understanding specifically what he means by “the distance that separates us.” But the surrounding context is a goldmine of reflections on the superior type, and it is surprising that Evola does not quote it more fully. Nietzsche remarks that “war educates for freedom” (a point on which Evola reflects at length in his Metaphysics of War), then writes:

For what is freedom? Having the will to responsibility for oneself. Maintaining the distance that separates us. Becoming indifferent to trouble, hardships, deprivation, even to life. Being ready to sacrifice people to one’s cause, not excluding oneself. Freedom means that the manly instincts, the instincts that celebrate war and winning, dominate other instincts, for example the instinct for “happiness.” The human being who has become free, not to mention the spirit that has become free, steps all over the contemptible sort of wellbeing dreamt of by grocers, Christians, cows, women, Englishmen, and other democrats. The free human being is a warrior.[20] [24]

The rest of the passage is well worth reading.

8. Evola tells us that the superior man rejects “the insidious confusion between discipline and enfeeblement.” The goal of discipline is not to produce weakness, but a greater strength. “He who does not dominate is weak, dissipated, inconstant.” To discipline oneself is to dominate one’s passions. As we saw in our discussion of the third principle, this does not mean stamping out the passions or denying them. Neither does it mean indulging them: the man who heedlessly indulges his passions becomes “weak, dissipated, inconstant.” Rather, the superior man learns how to control his passions and to make use of them as a means for self-transformation. It is only when the passions are mastered – when we have reached the point that we cannot be swept away by them – that we can give expression to them in such a way that they become vehicles for self-overcoming.

Evola quotes Nietzsche: “Excess is a reproach only against those who have no right to it; and almost all the passions have been brought into ill repute on account of those who were not sufficiently strong to employ them.”[21] [25] The convergence of Nietzsche’s position with Evola’s portrayal of the Left-Hand Path could not be clearer. The superior man has a right to “excess” because, unlike the common man, he is not swept away by the passions. He holds them “on a leash” (see earlier), and uses them as means to transcend the ego, and to achieve a higher state. The common man, who identifies with his passions, becomes wholly a slave to them, and is sucked dry. He gives “excess” a bad reputation.

9. Evola’s penultimate principle is in the spirit of Nietzsche, but does not quote from him. Evola writes: “To point the way of those who, free from all bonds, obeying only their own law, are unbending in obedience to it and above every human weakness.”[22] [26] The first words of this passage are somewhat ambiguous: what does Evola mean by “to point the way of those who . . .” (the original Italian – l’indicare la via di coloro che – is no more helpful). Perhaps what is meant here is simply that the superior type points the way for others. He serves as an example – or he serves as the vanguard. This is not, of course, an ideal to which just anyone can aspire. But the example of the superior man can serve to “awaken” others who have the same potential. This was, indeed, something like Nietzsche’s own literary intention: to point the way to the Overman; to awaken those whose souls are strong enough.

10. Finally, Evola tells us that the superior type is “heir to the equivocal virtus of the Renaissance despots,” and that he is “capable of generosity, quick to offer manly aid, of ‘generous virtue,’ magnanimity, and superiority to his own individuality.”[23] [27] Here Evola alludes to Nietzsche’s qualified admiration for Cesare Borgia (who Nietzsche offers as an example of what he calls the “men of prey”). The rest of the quote, however, calls to mind Aristotle’s description of the great-souled man – especially the use of the term “magnanimity,” which some translators prefer to “greatness of soul.”[24] [28] The superior man is not a beast. He is capable of such virtues as generosity and benevolence. This is because he is free from that which holds lesser men in thrall. The superior man can be generous with such things as money and possessions, for these have little or no value for him. He can be generous in overlooking the faults of others, for he expects little of them anyway. He can even be generous in forgiving his enemies – when they are safely at his feet. The superior man can do all of this because he possesses “superiority to his own individuality”: he is not bound to the pretensions of his own ego, and to the worldly goods the ego craves.

Evola’s very long sentence about the superior man now ends with the following summation:

Evola’s very long sentence about the superior man now ends with the following summation:

all these are the positive elements that the man of Tradition also makes his own, but which are only comprehensible and attainable when ‘life’ is ‘more than life,’ that is, through transcendence. They are values attainable only by those in whom there is something else, and something more, than mere life.

In other words, Nietzsche presents us with a rich and inspiring portrayal of the superior man. And yet, the principles he discusses will have a positive result, and serve the “man of Tradition,” only if we turn Nietzsche on his head. Earlier in Chapter Eight, Evola writes: “Nietzsche’s solution of the problem of the meaning of life, consisting in the affirmation that this meaning does not exist outside of life, and that life in itself is meaning . . . is valid only on the presupposition of a being that has transcendence as its essential component.” (Evola places this entire statement in italics.) In other words, to put the matter quite simply, the meaning of life as life itself is only valid when a man’s life is devoted to transcendence (in the senses discussed earlier). Or we could say, somewhat more obscurely, that Nietzsche’s points are valid when man’s life transcends life.

Evola’s claim goes to the heart of his criticism of Nietzsche. A page later, he speaks of conflicting tendencies within Nietzsche’s thought. On the one hand, we have a “naturalistic exaltation of life” that runs the risk of “a surrender of being to the simple world of instincts and passions.” The danger here is that these will then assert themselves “through the will, making it their servant.”[25] [29] Nietzsche, of course, is famous for his theory of the “will to power.” But surrender to the baser impulses of ego and organism will result in those impulses hijacking will and using it for their own purposes. One then becomes a slave to instincts and passions, and the antithesis of a free, autonomous being.

On the other hand, one finds in Nietzsche “testimonies to a reaction to life that cannot arise out of life itself, but solely from a principle superior to it, as revealed in a characteristic phrase: ‘Spirit is the life that cuts through life’ (Geist ist das Leben, das selber ins Leben schneidet).” In other words, Nietzsche’s thought exhibits a fundamental contradiction – a contradiction that cannot be resolved within his thought, but only in Evola’s. One can find other tensions in Nietzsche’s thought as well. I might mention, for example, his evident preference for the values of “master morality,” and his analysis of “slave morality” as arising from hatred of life — which nevertheless co-exist with his relativism concerning values. Yet there is so much in Nietzsche that is brilliant and inspiring, we wish we could accept the whole and declare ourselves Nietzscheans. But we simply cannot. This turns out to be no problem, since Evola absorbs what is positive and useful in Nietzsche, and places it within the context of Tradition. In spite of what Nietzsche himself may say, one feels he is more at home with Tradition, than with “perspectivism.”[26] [30]

Evola’s ten “Nietzschean principles,” reframed for the “man of Tradition,” provide an inspiring guide for life in this Wolf Age. They point the way. They show us what we must become. These are ideas that challenge us to become worthy of them.

Notes

[1] [31] Julius Evola, Ride the Tiger: A Survival Manual for the Aristocrats of the Soul, trans. Joscelyn Godwin and Constance Fontana (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 2003).

[2] [32] Evola, 46, my italics.

[3] [33] Evola, 47.

[4] [34] Übermensch; translated in Ride the Tiger as “superman.”

[5] [35] Quoting Nietzsche, Will to Power, section 778.

[6] [36] Evola, 41. Translator notes “adapted from the aphorism in Kritische Gesamtausgabe, vol. 7, part 1, 371.”

[7] [37] Evola, 41.

[8] [38] There is a great deal more that can be said here about the difference between Kantian and Nietzschean “autonomy.” Indeed, there is an argument to be made that Kant is much closer to Nietzsche than Evola (or Nietzsche) would allow. Ultimately, one sees the stark difference between Kant and Nietzsche in the “egalitarianism” of the different formulations of Kant’s categorical imperative. How can a man who is qualitatively different and superior to others commit to following no other law than what he would will all others follow? How can he affirm the inherent “dignity” in others, who seem to have no dignity at all? Should he affirm their potential dignity, which they themselves simply do not see and may never live up to? But suppose they are so limited, constitutionally, that actualizing that “human dignity” is more or less impossible for them? Kant wants us to affirm that whatever men may actually be, they are nonetheless potentially rational, and thus they possess inherent dignity. For those of us who have seen more of the world than Königsberg, and who have soured on the dreams of Enlightenment, this rings hollow. And how can the overman be expected to adhere to the (self-willed) command to always treat others as ends in themselves, but never as means only – when the vast bulk of humanity seems hardly good for anything other than being used as means to the ends of greater men?

[9] [39] The translator’s note: “Adapted from Twilight of the Idols, ‘Skirmishes of an Untimely Man,’ sect. 38, where, however, it is ‘freedom’ that is thus gauged.” Beware: Evola sometimes alters Nietzsche’s wording.

[10] [40] Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra, “Zarathustra’s Prologue,” 5.

[11] [41] Evola, 49.

[12] [42] Evola, 49. The Will to Power, sect. 928.

[13] [43] Will to Power, sect. 222.

[14] [44] Will to Power, sect. 790.

[15] [45] Will to Power, sect. 781.

[16] [46] Thus Spake Zarathustra, “Zarathustra’s Prologue,” 5.

[17] [47] Aristotle also said that the aim of human life is “happiness” (eudaimonia) – but “happiness” has a connotation here different from the familiar one.

[18] [48] Will to Power, sect. 921.

[19] [49] Twilight of the Idols, “Skirmishes of an Untimely Man,” sect. 38. Italics added by Evola.

[20] [50] See Twilight of the Idols, trans. Richard Polt (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1997), 74-75.

[21] [51] Here I have substituted the translation of Walter Kaufmann and R. G. Hollingdale for the one provided in Ride the Tiger, as it is more accurate and concise. See The Will to Power, trans. Kaufmann and Hollingdale (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 408.

[22] [52] Evola, 49.

[23] [53] The translators of Ride the Tiger direct us here to Beyond Good and Evil, sect. 260.

[24] [54] Grandezza d’animo literally translates to “greatness of soul.”

[25] [55] Evola, 48.

[26] [56] Evola writes (p. 52), “[Nietzsche’s] case illustrates in precise terms what can, and indeed must, occur in a human type in which transcendence has awakened, yes, but who is uncentered with regard to it.”

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

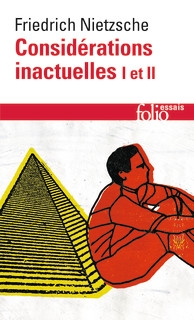

L'histoire est indispensable pour comprendre le présent : assurément... et voilà un lieu commun somme toute rassurant. Mais quelle(s) histoire(s), faite(s) par qui, et comment ? Y-a-t-il une manière neutre d'aborder le passé, ou plus recommandable que d'autres qui seraient trop orientées ou militantes ? Les historiens peuvent-ils s'ériger en arbitres des usages du passé – en particulier de ses usages ou instrumentalisations politiques ? Le savoir et l'érudition sont-ils en mesure de dire le dernier mot sur ce qui a eu lieu, et quelles seraient les conséquences de cette prétention ? La pensée d'un philosophe du XIXe siècle, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), peut aider à poser ces problèmes très actuels. En 1874, dans sa deuxième "Considération inactuelle", intitulée "De l'utilité et des inconvénients de l'histoire pour la vie", Nietzsche mettait en évidence les enjeux cruciaux de la "science historique" et de notre rapport au passé.

L'histoire est indispensable pour comprendre le présent : assurément... et voilà un lieu commun somme toute rassurant. Mais quelle(s) histoire(s), faite(s) par qui, et comment ? Y-a-t-il une manière neutre d'aborder le passé, ou plus recommandable que d'autres qui seraient trop orientées ou militantes ? Les historiens peuvent-ils s'ériger en arbitres des usages du passé – en particulier de ses usages ou instrumentalisations politiques ? Le savoir et l'érudition sont-ils en mesure de dire le dernier mot sur ce qui a eu lieu, et quelles seraient les conséquences de cette prétention ? La pensée d'un philosophe du XIXe siècle, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), peut aider à poser ces problèmes très actuels. En 1874, dans sa deuxième "Considération inactuelle", intitulée "De l'utilité et des inconvénients de l'histoire pour la vie", Nietzsche mettait en évidence les enjeux cruciaux de la "science historique" et de notre rapport au passé.

Ce qu’il faut mettre en évidence, c’est le lien fondamental établi par Nietzsche entre les valeurs chrétiennes et leurs avatars séculiers qui servent aujourd’hui de base légale et psychologique aux classes dirigeantes en Occident pour faire entrer des masses non-européennes en Europe. En utilisant les valeurs moralisatrices, dont les origines lointaines remontent au christianisme primitif, le Système est en train de procéder à la destruction des peuples européens.

Ce qu’il faut mettre en évidence, c’est le lien fondamental établi par Nietzsche entre les valeurs chrétiennes et leurs avatars séculiers qui servent aujourd’hui de base légale et psychologique aux classes dirigeantes en Occident pour faire entrer des masses non-européennes en Europe. En utilisant les valeurs moralisatrices, dont les origines lointaines remontent au christianisme primitif, le Système est en train de procéder à la destruction des peuples européens.  Commençons d’abord par l’expression « le grand remplacement ». Cette expression, due à l’écrivain Renaud Camus, est mal vue par le Système

Commençons d’abord par l’expression « le grand remplacement ». Cette expression, due à l’écrivain Renaud Camus, est mal vue par le Système

A titre d’exemple de ce mental allemand du « dopplengaegertum », on peut citer plusieurs auteurs de contes fantastiques du début du XIXe siècle qui, par détour, reflètent parfaitement l’esprit fracturé de l’Allemagne d’aujourd’hui. Citons ainsi l’écrivain de contes horrifiques E. T. A. Hoffmann et sa nouvelle L’homme au sable

A titre d’exemple de ce mental allemand du « dopplengaegertum », on peut citer plusieurs auteurs de contes fantastiques du début du XIXe siècle qui, par détour, reflètent parfaitement l’esprit fracturé de l’Allemagne d’aujourd’hui. Citons ainsi l’écrivain de contes horrifiques E. T. A. Hoffmann et sa nouvelle L’homme au sable  Ni l’Eglise catholique ni les papistes du monde entier ne sont à la traîne. Le dernier en date est le pape François avec ses prêches sur les droits des immigrés ou ses homélies affirmant que « les migrants sont le symbole de tous les exclus de la société globalisée »

Ni l’Eglise catholique ni les papistes du monde entier ne sont à la traîne. Le dernier en date est le pape François avec ses prêches sur les droits des immigrés ou ses homélies affirmant que « les migrants sont le symbole de tous les exclus de la société globalisée »

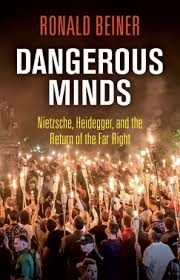

Ronald Beiner is a Canadian Jewish political theorist who teaches at the University of Toronto. I’ve been reading his work since the early 1990s, starting with What’s the Matter with Liberalism? (1992). I have always admired Beiner’s clear and lively writing and his ability to see straight through jargon and cant to hone in on the flaws of the positions he examines. He is also refreshingly free of Left-wing sectarianism and willing to engage with political theorists of the Right, like Leo Strauss, Eric Voegelin, Michael Oakeshott, and Hans-Georg Gadamer. Thus, although I was delighted that a theorist of his caliber had decided to write a book on the contemporary far Right, I was also worried that he might, after a typically open and searching engagement with our outlook, discover some fatal flaw.

Ronald Beiner is a Canadian Jewish political theorist who teaches at the University of Toronto. I’ve been reading his work since the early 1990s, starting with What’s the Matter with Liberalism? (1992). I have always admired Beiner’s clear and lively writing and his ability to see straight through jargon and cant to hone in on the flaws of the positions he examines. He is also refreshingly free of Left-wing sectarianism and willing to engage with political theorists of the Right, like Leo Strauss, Eric Voegelin, Michael Oakeshott, and Hans-Georg Gadamer. Thus, although I was delighted that a theorist of his caliber had decided to write a book on the contemporary far Right, I was also worried that he might, after a typically open and searching engagement with our outlook, discover some fatal flaw.

Beiner doesn’t offer a very clear account of why Nietzsche thinks liberalism undermines human nobility. The short answer is that it is simply the political application of the slave revolt in morals, in which the aristocratic virtues of the ancients were transmuted into Christian and eventually liberal vices, and the vices of the enslaved and downtrodden were transmuted into virtues.

Beiner doesn’t offer a very clear account of why Nietzsche thinks liberalism undermines human nobility. The short answer is that it is simply the political application of the slave revolt in morals, in which the aristocratic virtues of the ancients were transmuted into Christian and eventually liberal vices, and the vices of the enslaved and downtrodden were transmuted into virtues.

In Heidegger’s later terminology, Nietzsche and National Socialism were both “humanistic,” premised on the idea that the human mind creates culture, whereas in fact culture creates the human mind. No genuine belief can be chosen. It has to seize us. This is one of the senses of Heidegger’s later concept of Ereignis, often translated “the event of appropriation”: the beginning of a new historical epoch seizes and enthralls us. This is the meaning of Heidegger’s later claim that “Only a god can save us now” — as opposed to a philosopher-dictator.

In Heidegger’s later terminology, Nietzsche and National Socialism were both “humanistic,” premised on the idea that the human mind creates culture, whereas in fact culture creates the human mind. No genuine belief can be chosen. It has to seize us. This is one of the senses of Heidegger’s later concept of Ereignis, often translated “the event of appropriation”: the beginning of a new historical epoch seizes and enthralls us. This is the meaning of Heidegger’s later claim that “Only a god can save us now” — as opposed to a philosopher-dictator. Beiner is even more blatant in his advocacy of self-censorship in Heidegger’s case:

Beiner is even more blatant in his advocacy of self-censorship in Heidegger’s case:

N.A. -

N.A. -

The cause of this misunderstanding of Euripidean tragedy may be traced back to Richard Wagner’s analyses of Greek drama in his Oper und Drama (Opera and Drama) (1851), Bk.III, Ch.3:

The cause of this misunderstanding of Euripidean tragedy may be traced back to Richard Wagner’s analyses of Greek drama in his Oper und Drama (Opera and Drama) (1851), Bk.III, Ch.3:

Rien n’est responsabilité et tout est innocence pour Nietzsche (Humain, trop humain). Il reste la probité c’est-à-dire la rigueur et l’exigence vis-à-vis de soi-même. Quand Nietzsche dit qu’il n’y a pas de responsabilité des actes humains, en quel sens peut-on le comprendre ? En ce sens que : c’est le motif le plus fort en nous qui décide pour nous. Nous sommes agis par ce qui s’impose à nous en dernière instance : soit une force qui nous dépasse (ainsi la force de la peur qui nous fait fuir), soit une force qui nous emporte (ainsi la force de faire face conformément à l’idée que nous avons de nous-mêmes). Mais dans les deux cas, il n’y a pas de responsabilité à proprement parler.

Rien n’est responsabilité et tout est innocence pour Nietzsche (Humain, trop humain). Il reste la probité c’est-à-dire la rigueur et l’exigence vis-à-vis de soi-même. Quand Nietzsche dit qu’il n’y a pas de responsabilité des actes humains, en quel sens peut-on le comprendre ? En ce sens que : c’est le motif le plus fort en nous qui décide pour nous. Nous sommes agis par ce qui s’impose à nous en dernière instance : soit une force qui nous dépasse (ainsi la force de la peur qui nous fait fuir), soit une force qui nous emporte (ainsi la force de faire face conformément à l’idée que nous avons de nous-mêmes). Mais dans les deux cas, il n’y a pas de responsabilité à proprement parler.

Nietzsche tente de dépasser la question du choix entre l’infinité ou la finitude du monde. Il tente de la dépasser par un pari sur la joie et sur la jubilation. C’est en quelque sorte la finitude du monde corrigée par l’infinité des désirs et des volontés de puissance. La physique de Nietzsche est peut-être ainsi non pas une métaphysique – ce qui est l’hypothèse et la critique de Heidegger – mais une hyperphysique.

Nietzsche tente de dépasser la question du choix entre l’infinité ou la finitude du monde. Il tente de la dépasser par un pari sur la joie et sur la jubilation. C’est en quelque sorte la finitude du monde corrigée par l’infinité des désirs et des volontés de puissance. La physique de Nietzsche est peut-être ainsi non pas une métaphysique – ce qui est l’hypothèse et la critique de Heidegger – mais une hyperphysique.

Nietzsche also espouses this sentiment in The Birth of Tragedy where he describes culture as the “most basic foundation of the life of a people”.6 The modern nation however has become increasingly complex and the more it grows, the weaker the ties to the people and the concept of Being in the nation becomes. Familiarity is essential in creating communal bonds, but the very size of the nation renders this difficult, and micro-communities are therefore formed which ultimately serve to de-stabilize the larger power structure of the government. This is not only bad for the nation, but also for those who govern the nation, because it creates a distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’, and this perceived disparity dissolves the foundation of collective identity within the nation. As such, the elected representatives of modern democracies immediately find themselves juxtaposed with a large group of disgruntled citizens who have no true loyalty to the nation, and are instead controlled by purely by legislative force alone. In the worst case scenario, this leads to both ressentiment and revolution.

Nietzsche also espouses this sentiment in The Birth of Tragedy where he describes culture as the “most basic foundation of the life of a people”.6 The modern nation however has become increasingly complex and the more it grows, the weaker the ties to the people and the concept of Being in the nation becomes. Familiarity is essential in creating communal bonds, but the very size of the nation renders this difficult, and micro-communities are therefore formed which ultimately serve to de-stabilize the larger power structure of the government. This is not only bad for the nation, but also for those who govern the nation, because it creates a distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’, and this perceived disparity dissolves the foundation of collective identity within the nation. As such, the elected representatives of modern democracies immediately find themselves juxtaposed with a large group of disgruntled citizens who have no true loyalty to the nation, and are instead controlled by purely by legislative force alone. In the worst case scenario, this leads to both ressentiment and revolution. In regards to music and its effect on politics and culture, another figure connected to Nietzsche who cannot be ignored is the ever-present specter of Richard Wagner. Ultimately the friendship of the two was not based purely on passion for music, but also the use of mythology, something with Richard Wagner indisputably drew upon in his operas. Wagner wrote in Deutsche Kunst and Deutsche Politik on the social and political meaning of such aesthetic theories: “Modern life, Wagner wrote, [shall be] reorganized by the rebirth of art, and especially by a new theater whose life-giving function shall be equal to that of ancient Greek drama”.17 Although Nietzsche would eventually separate himself from Wagner due to the musician’s anti-Semitism, Nietzsche also explored the uses of myth during his period of friendship with Wagner. “The legend of Prometheus”, Nietzsche writes,

In regards to music and its effect on politics and culture, another figure connected to Nietzsche who cannot be ignored is the ever-present specter of Richard Wagner. Ultimately the friendship of the two was not based purely on passion for music, but also the use of mythology, something with Richard Wagner indisputably drew upon in his operas. Wagner wrote in Deutsche Kunst and Deutsche Politik on the social and political meaning of such aesthetic theories: “Modern life, Wagner wrote, [shall be] reorganized by the rebirth of art, and especially by a new theater whose life-giving function shall be equal to that of ancient Greek drama”.17 Although Nietzsche would eventually separate himself from Wagner due to the musician’s anti-Semitism, Nietzsche also explored the uses of myth during his period of friendship with Wagner. “The legend of Prometheus”, Nietzsche writes, This is Nietzshe’s Geisterkrieg – a war of ideas that is to fought at the academic and intellectual level to control the flow of ideas, culture, and the politics that emerge from it. This is similar to the modern idea of “metapolitics”. The Geisterkrieg however, “cuts right through the absurd arbitrariness that are peoples, class, race, profession, education, culture,” a war instead “between ascending and declining, between will-to-live and the desire for revenge on life”.29 In the context of the Geisterkrieg and Grosse Politik, the artists and the philosophers become the creators of all future governments and orders – for as Nietzsche tells us, “The artist and philosopher […] strike only a few and should strike all”.30 This means that they have not yet realized their ability to create cultural changes. Only the artists and philosophers are capable of launching Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, the war of ideas. However, due to the current dominance of capitalism and production based society over democracy (across both the Left and Right) the influence of artists and philosophers are severely impaired. And because of this, their rule continues unchallenged because Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, if successful, would end all petty nationalism and party specific squabbles. Partisan based politics would no longer exist, replaced instead by leaders who embody thymos the most as is stated here,

This is Nietzshe’s Geisterkrieg – a war of ideas that is to fought at the academic and intellectual level to control the flow of ideas, culture, and the politics that emerge from it. This is similar to the modern idea of “metapolitics”. The Geisterkrieg however, “cuts right through the absurd arbitrariness that are peoples, class, race, profession, education, culture,” a war instead “between ascending and declining, between will-to-live and the desire for revenge on life”.29 In the context of the Geisterkrieg and Grosse Politik, the artists and the philosophers become the creators of all future governments and orders – for as Nietzsche tells us, “The artist and philosopher […] strike only a few and should strike all”.30 This means that they have not yet realized their ability to create cultural changes. Only the artists and philosophers are capable of launching Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, the war of ideas. However, due to the current dominance of capitalism and production based society over democracy (across both the Left and Right) the influence of artists and philosophers are severely impaired. And because of this, their rule continues unchallenged because Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, if successful, would end all petty nationalism and party specific squabbles. Partisan based politics would no longer exist, replaced instead by leaders who embody thymos the most as is stated here,